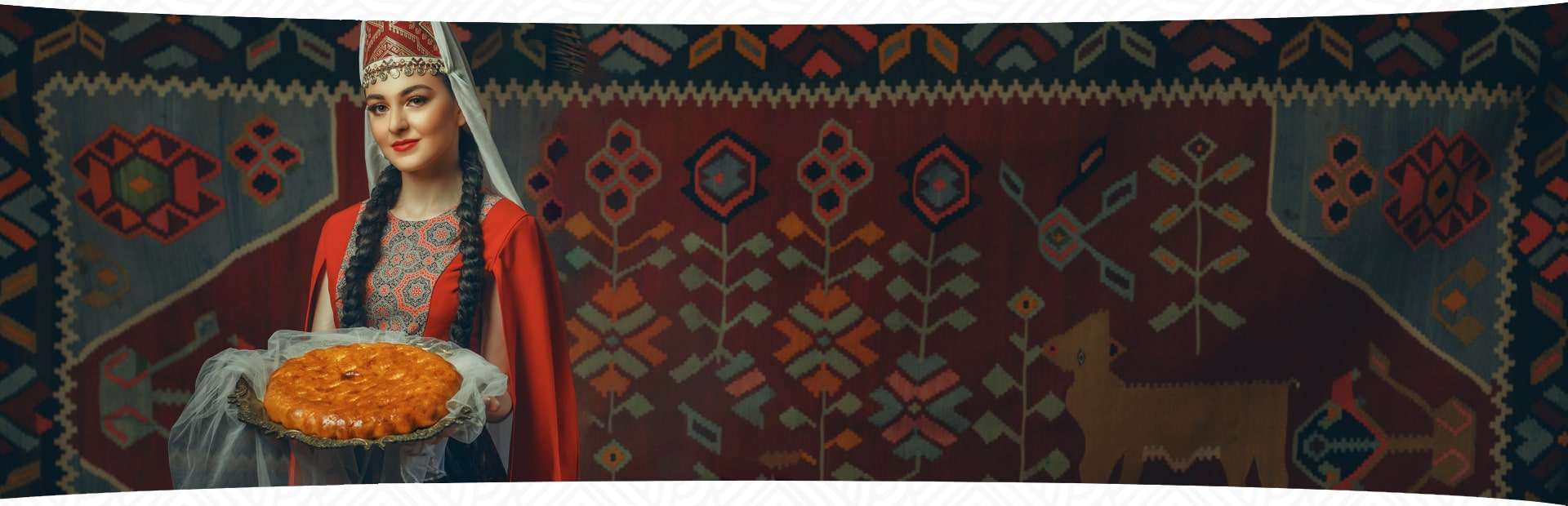

Dining Like a King: What Armenian Kings and Queens Used to Eat

Armenian cuisine has, for centuries, been not only a part of daily life but also a reflection of state grandeur. It represents the fertility of our land, the harmony of nature, and the spiritual wealth of our people. However, few know that Armenian kings and queens were true gastronomic enthusiasts who appreciated the art of taste as an extension of power and culture.

Traditional Armenian cuisine has developed over thousands of years, influenced by the culinary traditions of Persia, Byzantium, and Assyria. Yet Armenians managed to preserve their originality, creating a taste culture distinguished by its simplicity and deep symbolism.

In royal palaces, food was not only a physical necessity but also a symbolic act. Each dish represented strength, abundance, longevity, or blessing. Royal chefs—among the most skilled of their time—prepared dishes worthy of the king’s table. Thus, a unique branch was formed: Armenian royal cuisine.

Every detail mattered in the royal kitchen—the origin of the ingredients, the method of preparation, and the moment of serving. Bread symbolized life, wine was a divine blessing, and meat stood for strength. Bread was always placed first on the king’s table as a form of blessing.

Historical sources confirm that even in King Tigran the Great’s palace, chefs and winemakers were specially selected, not only for their mastery but also for their sense of art. Because a royal meal was meant to be not just food, but a performance—a harmony of flavors, colors, and aromas.

Armenian Royal Cuisine: The Art of Flavor

The traditions that formed around royal tables eventually became the foundation of Armenian historical dishes. Looking at the culinary customs of Greater Armenia, one sees that natural ingredients dominated—without unnecessary processing. This is the secret of Armenian cuisine: simple ingredients, perfect combinations.

Among the favorite dishes of the kings was roasted lamb with a mix of herbs, served with fresh lavash and grape sauce. Variations of barbecue were known as early as the Artaxiad dynasty—prepared over open flame using special copper skewers. This dish symbolized royal strength and was often served after military victories.

Queens’ tables often featured plant-based dishes made with legumes, grains, and aromatic oils. It is said that Queen Tiramayis especially enjoyed sauces made with pomegranate and honey, used both with meats and desserts.

Fish also held an important place in palace cuisine. Fresh fish brought from the shores of the Araks and Lake Sevan was seasoned with fragrant herbs and cooked in clay pots. It was served with wine, considered sacred and connected to the ancient winemaking traditions of Metsamor.

But an inseparable part of royal cuisine was bread. Lavash, the irreplaceable element of Armenian tables, was baked in a special way. Tonir-baked bread was considered blessed and often accompanied by salt and apples, symbolizing prosperity. Lavash was more than food—it was a ceremony, one of the most cherished moments of the royal feast.

Over the centuries, these traditions passed down to the people, forming what we now call Armenian cuisine. It preserves the taste and elegance of royalty, yet is served in every household with the same heartfelt warmth.

At Gata Tavern, for example, this very approach is alive. Here, traditional Armenian dishes—tonir bread, dolma, harissa, and of course, gata—are served with the same care that palace chefs once offered to kings. That’s why the tavern’s atmosphere is often compared to ancient hospitality—rich in flavors, refined wines, and harmonious aromas.

Historical Flavors at the Modern Table

Today, as the world returns to its roots, Armenian historical dishes are gaining renewed attention. At gastronomic festivals, museum exhibitions, and even modern restaurant menus, these ancient Armenian flavors are becoming true discoveries.

The tastes of ancient times are coming back to life. For example, royal porridge made with wheat, butter, and honey is now considered a trendy Armenian breakfast. Dolma—grape leaves stuffed with meat, enhanced with wine—has remained a core symbol of our cuisine for centuries.

Likewise, gata, originally a festive pastry served during royal celebrations, has become a symbol of Armenian hospitality. Its sweet taste recalls the days when royal meals ended with honey- and walnut-based desserts.

Many places in modern Yerevan are attempting to revive these traditions. But Gata Tavern stands out by not simply copying the old—it brings it to life with a new spirit. Here, Armenian royal cuisine becomes a modern experience. Guests can taste the same flavors once enjoyed by our kings and queens.

Bread, wine, meat, herbs—everything is prepared by hand, without haste. It reflects the old royal philosophy: “A meal should not be fast, but worthy.”

Today, as global cuisines blend together, Armenian cuisine retains its identity—proudly reminding the world that we have not only a delicious past but also a culturally rich heritage.

Armenian cuisine is not just a part of everyday life but a reflection of royal culture. It tells the story of how our kings and queens viewed the world—through the language of taste and values.

Armenian royal cuisine reminds us that a meal is not merely food; it is an attitude toward life. And the historic Armenian dishes that once adorned royal tables still live on today—in every Armenian home, in every piece of gata.

Gata Tavern is the continuation of this very idea. Here, one can feel the spirit of royal hospitality—not with palace luxury, but with the same grandeur. And when you sit at the table, tasting lavash, wine, and gata, you realize: to be royal, you don’t need a palace. You just need to live by the flavor of Armenian cuisine.